You aren't going to like this. You are going to yell at me. You are going to ask what is my solution (which I actually present in an embryonic form later).

Recycling...ah, it sounds so nice. Something we can all do to help the environment...all meaning each of us as individuals and right up the line to various manufacturing industries, corporations, and tech firms. Let's all recycle. It's so nice.

Well...hmm...ask those who live around the Canada Docks area in Liverpool and they might quarrel with you a wee bit. Their sick of living in the sickening environment caused by this nod to the environment. You can read about all that in the post below my sweet introduction.

Now, I am not going to come out against recycling. That would be ridiculous, but I am going to present you with a piece that shows you up close and personal that the recycling industry is just one more dirty, filthy, capitalist enterprise...and maybe you shouldn't feel so all self righteous everytime you dump something in your little bin or drop it off at some local center.

Capitalism, always a clever beast, has found a way to make the recycling of market overconsumption into environmentalism. Capitalism has found a way to make consumers feel good about their consumption of masses of unnecessary goods by allowing them to put them out in their curbside bins every week to be carried off...somewhere, where something is done with it, but what?

If you understand the nature of Capital, you realize an industry desire must exist for the recyclable material to be recycled by the recycling-industrial complex. Furthermore, if there are not enough of the same items to recycle, or a local recycling facility does not have the capability to reprocess the material, then the item is disposed of in landfills.

Even the capitalists are aware of the problem of their own making as their journal Forbes exemplifies:

Trade groups representing various packaging interests–plastic, paper, glass–have become the largest proponents and financial sponsors of recycling.

The plastics industry’s interest in recycling is two-fold of course–on the one hand, by supporting recycling and helping to establish infrastructure for plastic recycling, the industry ensures a steady supply of new materials. On the other, it helps consumer to justify the consumption of more disposable plastic goods and packaged items if they can comfort themselves with the idea that whatever they toss in the bin will be recycled.

The thing is, recycling isn’t the small operation it once was, it’s a commodity business that fluctuates with supply and demand. It’s also a global market, with recyclables collected in the United States being shipped to wherever demand is highest (often China). A few years ago, when demand for recycled paper products dropped, recyclers all over the country where warehousing stacks of cardboard, waiting for the prices to turn around. “The hope is that eventually the markets turn around and that the material is sold, but I have heard of instances where it gets landfilled, because a community doesn’t have the demand or the space or the company to deal with it,” says Gene Jones, executive director of Southern Waste Information Exchange—a nonprofit center for information about recycling waste. There’s a difference between things being recyclable and actually being recycled,” says Gerry Fishbeck, vice president of UNited Resource Recovery Corporation (URRC), one of the largest recyclers in the country. ”It’s centered around critical mass – is there enough of the material out there? And even if there is, is it worth it for recyclers to create a whole separate stream?”

Fishbeck cites PVC as a perfect example: Technically it’s recyclable, but most recyclers don’t handle the stuff. It can mimic PET and thus easily get into a PET recycling stream, but when it’s melted down it will create brown particles in the resin, creating color problems with the resulting material. “So even though it’s recyclable, that material will get separated out and disposed of as waste at the recycling facility,” Fishbeck explains.

Bioplastics are another example. With the exception of bio-based PET and HDPE, bioplastics fall into the recyclable but not recycled category. They are treated as contaminants of the recycling stream by most recyclers and separated out as waste. “If PLA (polylactic acid, the most common bioplastic today) gets into the recycling stream, it will cause contamination, it will be a defect, and that means we’ll do everything we can to keep it out of the stream and it will become waste,” Fishbeck says. “There’s just not enough of it around to have the critical mass to justify getting it separated and recycled. It can be done, but it isn’t.”

Emissions are another sticky subject for recycling. In the case of some materials–aluminum corrugated cardboard, newspaper, dimensional lumber, and medium-density fiberboard–the net greenhouse gas emissions reductions enabled by recycling are actually greater than they would be if the waste source was simply reduced, according to the EPA. For others–glass, plastic–while in some cases the energy required to recycle versus making virgin material is lower, there are concerns about the particulates emitted by recycling factories. In recent studies of air quality in Oakland, recycling centers were, perhaps surprisingly, included amongst the city’s polluters.

You probably didn't know that studies indicate, for example, only 6.8% of all plastics are actually recycled, when 77% of Americans are thought to recycle. Something is amiss.

PolicyMic points out, shockingly:

... recycling is considered a proactive measure to help secure the welfare of the environment. Overwhelming quantities of facts and figures, however, dispute this assumption. It is theorized that recycling actually causes more carbon emissions than it actually saves. For just one example, curbside recycling requires more trucks for collecting the same amount of waste. In most communities, this requires, on average, twice the amount of waste disposal vehicles. Therefore, recycling requires more iron ore and coal mining, steel and rubber manufacturing, and petroleum extractions for refined fuel. Ultimately, the consequence is more air pollution.

As Fresh writes:

The key problem with recycling is that it is actually downcycling: the materials go down in quality over time. In the landmark treatise on green product design Cradle to Cradle, William McDonough and Michael Braungart wrote:

“When plastics other than those found in soda and water bottles are recycled, they are mixed with different plastics to produce a hybrid of lower quality, which is then molded into something amorphous and cheap, such as a park bench or a speed bump… Aluminum is another valuable but constantly downcycled material. The typical soda can consists of two kinds of aluminum: the walls are composed of aluminum, manganese alloy with some magnesium, plus coatings and paint, while the harder top is aluminum magnesium alloy. In conventional recycling these materials are melted together, resulting in a weaker—and less useful—product.” (Cradle to Cradle, 56-57)

In other words, with most recyclables, you can’t just keep reusing the same materials over and over again. Eventually, they are downcycled to a point where it is no longer economically or chemically feasible to transform them, and they are thrown out into the landfill that you were trying to avoid. So much for closed-loop materials usage.

Even worse, products made from recycled materials can have harmful additives and toxins. When plastics are melted together, chemical or mineral additives may be used to recoup the clarity and strength of the original plastic. Downcycled paper requires bleaching to make it blank again, and the result is an amalgamation of chemicals, pulp and toxic inks. Wearing clothing made with fibers from recycled plastics means your fleece sweater likely contains catalytic residues, ultraviolet stabilizers, plasticizers and other additives, which were never designed to be in extended contact with human skin. If a product was not designed from the start to be recycled, continued use past its intended lifetime can have unintended consequences.

However, we should also remember that it is scientifically proven that recycling improves self-esteem. And really, isn't that what all this about...giving us all the chance to damage each other and the environment, but feel pretty darn good about it.

The truth is in many ways, recycling is not a sustainable solution, and distracts from how to resolve our growing waste problem.

What if instead of all this nonsense we just got rid of Capital itself, designed products that could be tossed onto the ground, decompose naturally, return themselves and their nutrients to the soil, to nature...or even where that is not feasible, made them so they could be returned to the industrial system to cycle forever as high-quality materials. We do have that technology.

There's a thought.

And now, from Mute:

LIVERPOOL'S DOCKS, DUST AND DIRT

By Brian Ashton, David Jacques, Steve Toombs & David Whyte, 4 April 2014

A trip down the dock road in the old days would have been an interesting and pleasant experience. You could have taken in the sights from the vantage points offered by the overhead railway, and if you decided to stretch your legs as you reached Canada Dock station you would have been greeted by the smells of Canadian pine and birch as you alighted. Canada was the dock for the importing of timber; wood still comes in, but further down the road towards Seaforth.

Today a trip down to Canada Dock would not be one you would want to repeat. The Overhead has long gone, and the aromas of wood resins have been replaced by the stench of god knows what. And if you were to ask an industrial chemist to analyse the dust and dirt that coats the environs of the North End docks he or she would tell you that they contain arsenic, chromium, lead and mercury. Not the sort of minerals you would want excesses of in your body. So, you say, I’m staying away from there. And who could blame you. But what about those who live and work in the area? And what is producing the deterioration in the air quality around the Canada Dock area? Or should that be, who?

In the globalised economy that is 21st century capitalism, commodities are increasingly produced in places like China, India and Slovakia. The major markets for commodities are Europe and North America. The demand for metals is increasing in the East, and the West is producing the waste, like old cars, busted washing machines and fridges. As well as consumer waste there are over 75 million tonnes of commercial and industrial waste produced per annum in the UK. Complex supply chains exist to produce and deliver the commodities we are all encouraged to consume, and equally complex chains exist to return the recycled waste to the Far Eastern and Eastern European producing countries. And, yes, the whole bloody process starts all over again as it gets turned into cars, washing machines and fridges.

Liverpool is an important centre for the recycling of the waste that is sent back to the East. It has a number of advantages; it is a major port, a port with land to spare, and it has an available supply of unskilled and semi-skilled labour. These advantages have attracted companies who are intent on making a profit out of the scrap and crap that consumerism produces. The possibility for profit has increased owing to European and UK legislation on disposal of end of life vehicles (ELV) and regulations on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). The ELV directive was implemented in the UK through the ELV Regulations 2003 and 2005. The WEEE regulations came into force in January 2007.

The 2003 ELV regulations stated that vehicles had to be de-polluted, all hazardous fluids, batteries and tyres had to be removed and recycled or disposed of lawfully. 2005 regulations put the onus on the original vehicle manufacturer to provide a free take-back service to the last owners of complete ELVs. The 2005 regulations provided an opportunity for companies in the business of dismantling vehicles. They formed themselves into consortia to gain the business of collecting and recycling ELVs.

Two companies with plants in the docklands of North Liverpool, European Metal Recycling (EMR) and S. Norton & Co. Ltd, better known as Norton Scrap, have helped to set up these organisations. According to their web site, the consortium headed by EMR has no formal contracts with vehicle producers. Norton, on the other hand, have formal contracts with producers through the organisation they helped to set up, Cartakeback.com. Some 30-odd vehicle manufacturers have signed up with the organisation. Norton are one of the ten companies who set it up, but there are over two hundred other companies in this recycling supply chain and they provide over 250 sites across the country for the disposal of your car. So, if your Alfa Romeo or Bugatti is on its last legs then get in touch with Cartakeback.com and they will do the business for you. It is estimated that Norton and their partners expect to reach an annual turnover of one billion pounds sterling, and to produce four million tonnes of recycled scrap. That is 40 percent of the UK’s total.

Image: European Metal Recycling in Bootle

Although EMR and Norton are two of the major players in the recycling of vehicles and electronic and electrical waste, they are not the only ones operating in the docklands area. Counting EMR’s three facilities there are fourteen such sites in close proximity to housing estates and public amenities. The breaking up of Royal Navy ships is also taking place at the Canada dry dock. And while all the firms involved in these breaking and recycling processes stress their commitment to improving the environment, it has to be said that carcinogenic matter has been found in the vicinity of the recycling plants and the housing estates there about.

While recycling is posited as a positive process the mechanics of recycling is itself potentially dangerous. Chemical processes are used in the recycling of scrap metal as a means to separate scrap into its component metals, to clean scrap prior to using physical processes to remove contaminants, and to extract selected metals from a batch of scrap containing many types of metal. Emissions from theses processes include metal fumes and vapours, organic vapours, and acid gases.

Four of the metals found in the vicinity of the housing estates are arsenic, chromium, lead and mercury; these are present in the commodities that are being recycled under the ELV and WEEE regulations.

Exposure to arsenic can cause a number of medical problems, including irritated lungs, damage to blood vessels and to nerves in the hands and feet. Occupational studies have found increased risk of lung cancer among employees exposed to inorganic arsenic over a period of time. Inorganic arsenic is a known human carcinogen.

Chromium exists in several physical states; the most common are chromium metal (Cr0), trivalent chromium (Crill) and hexavalent chromium (CrVI). They are used in various processes, to produce stainless steel, alloy steels, pigments in paints, plastics and dyes. The major illnesses associated with occupational exposure to CrVI are lung cancer, nasal septum, ulcerations, asthma, and allergic and irritant dermatitis. It is a known human carcinogen.

Lead is used primarily in batteries; other uses include sheathing on electrical cables and for corrosion resistance and colour characteristics in paints. Recycling of lead scrap with other scrap produces air emissions containing sulphur dioxide and particulate matter containing lead and cadmium. Lead is a systemic poison and overexposure to it can damage blood forming processes, as well as nervous, urinary, cardiovascular and reproductive systems. Lead accumulates in the body over time and remains in the blood for a month, in vital organs for several months, and in bones for years. It is regarded as a probable human carcinogen. And by the by, cadmium is classified as a known human carcinogen.

Mercury is used in batteries, lubricating oils, switches and valves. Tests carried out in the USA in 1999 showed that facilities that process steel scrap could be a large source of mercury emissions. Exposure to high levels of metallic, inorganic, or organic mercury can permanently damage the brain, kidneys, and developing foetus. Short-term exposure to high levels of metallic mercury vapour may cause adverse effects including lung damage, nausea, vomiting, increases in blood pressure, skin rashes, and eye irritation. The US Environmental Protection Agency has been studying mercury and considers it to be the pollutant of ‘greatest potential concern’. Dr. Lars Friberg, former Chief Advisor on mercury to the World Health Organisation said, ‘There is no safe level of mercury, and no one has actually shown that there is a safe level. I would say mercury is a very toxic substance.’

You may have an image in your head of workers swarming over ships that have been run onto a beach in Bangladesh. Working in a highly toxic atmosphere day labourers break the giant ships down to dust.

Image: Ship Breaking Yard Bangladesh

If you were to take yourself down to the Liverpool docks today you would see ships being broken down by local workers, who are wearing paper masks and, sometimes, hard hats. They are breaking Royal Naval ships because, it is said, the government wants to stop such polluting practises taking place in countries like Bangladesh. The companies who are organising the scrapping of the ships say that the processes are being carried out in carefully controlled environments.

Go down there and draw your own conclusions. Or ask the firefighters who had to tackle the blaze on the RN Intrepid what they think. Lagging was damaged during the fire. The question that has to be asked is, was it asbestos lagging? It is claimed by the companies involved in breaking up the ship that asbestos and other harmful materials were removed before recycling took place. One of those companies is Technical Demolition Services (TDS), based in Birkenhead. In 2001 they were found guilty of breaking the law seven times in regards to the removal of asbestos while carrying out a contract to remove asbestos from a hospital in Wales. Six of the offences were related to the Control of Asbestos at Work 1987 law, and the other offence was against the Asbestos (Licensing) Regulations. They were fined £4000 for each offence. TDS and the firm coordinating the ship dismantling activities, Leavesley Environmental, are hoping to make the business a permanent feature on the waterfront.

Communities in the vicinity of the dock road have voiced serious concerns about the deterioration of the environment in their neighbourhoods and have had discussions with councillors. Council officers seem to have been complacent in their attitude to the problems raised by the people who pay their wages. Officers have suggested that the dust containing arsenic, chromium, lead and mercury is as a result of road haulage movements. Are they blind to the fact that the regulations appertaining to the processing of ELVs and WEEEs coupled to the breaking up of ships at Canada Dock have had the effect of reorganising the scrap metal industry in the heart of working class communities? The industry is now integrated into the supply chains of global capital, it is a part of the just-in-time production systems that demand that materials are delivered where capital wants them, when capital wants them, in the volumes that capital wants, and to a quality standard that capital demands. Legislation tends to lag behind the activities of capital; the banking crisis has proved that, but it is no excuse for the apparent complacency of council officers on this matter.

The sort of activities discussed here are not exclusive to Merseyside; they are taking place in other working class communities across the country and across the rest of the European Union. These communities need to come together to tackle what could develop into a serious environmental problem. Social science and environmental science departments of higher education institutions could usefully serve these communities by becoming involved in the necessary debate around this issue.

Recycling adverts bring to mind a green and pleasant environment, but the reality for working class communities surrounded by these activities is somewhat different. It is a reality that is dusty, dirty and coloured a dark, shitty brown.

Brian Ashton is an ex car-industry shop steward who developed an interest in the logistics industry while doing support work with the sacked Liverpool dockers in the mid-'90s. He is currently researching the global supply chains of the clothing industry

Butterflies in a Thunderstorm

By Steve Tombs & David Whyte

Politicians of all parties in Merseyside have for several years now been unable to see past a fairy tale idea of regeneration. They remain fixated on the fetish of an army of Prince Charming investors arriving to sweep the city off its feet and restore its deserved prosperity. In this fairy tale, Liverpool will get rich so long as it makes itself an attractive place to do business. Meanwhile, in the real world, the city remains the poorest in the country. The Liverpool One shopping development, opened in 2008, ‘City of Culture’ year, perhaps symbolises a fetish by which the city’s resurgence must be based on a low wage, low skill economy in which the social consequences of doing business are swept aside by the insatiable drive for inward investment.

Grosvenor, the Liverpool One developer owned by the Duke of Westminster, has close interests in another project that has been regarded as a centrepiece of local regeneration in Merseyside. Grosvenor shares ownership of Sonae Sierra, the shopping centre wing of a conglomerate that also owned the Sonae chipboard factory in Kirkby. Employing some 200 people, the factory was opened to fanfare by the Duke of Edinburgh in 2000. The venture had the financial and political backing of several public authorities, including Knowsley Borough Council, and a grant of £1.95 million awarded by the Department of Trade and Industry when it was headed by Peter Mandelson. Sonae’s heavily subsidised ‘investment’ was hailed as a part of ‘major efforts towards regeneration’ in the borough.1

Yet the story of the factory since its inception is far from a simple tale of successful regeneration. Indeed, it took little more than four years for local MP George Howarth, who had been evangelical in his praise for the plant as it opened, to demand its closure.2 How did the fairy tale turn so rotten so quickly?

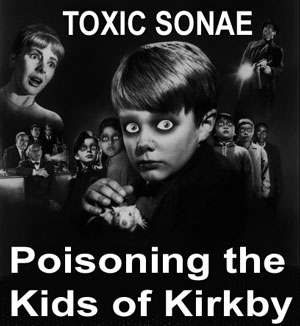

As early as 2001, local residents were organising against Sonae in a call to shut the plant down due to health fears.3 Evidence gathered by the community group Knowsley Against Toxic Sonae included the results of monitoring local public and environmental health effects since the plant’s opening, revealing symptoms associated with exposure to formaldehyde which worsened with the appearance of black/brown smoke and haze from the factory. They also reported systematic fugitive emissions and health and safety problems that were not reported to the relevant authorities by factory management, in breach of the law.4

Image: Poster by Kirby residents

There is an established stock of knowledge regarding the general hazards of chipboard production. These include exposures to formaldehyde resins which, even at low levels, irritate the eyes, mucous membranes, nose and throat, can sensitise skin (potentially leading to dermatitis) and the respiratory system (which can lead to asthma and/or rhinitis) and increase the risk of cancer; to melamine, a known eye, skin and mucous membrane irritant, a cause of dermatitis, and an ‘experimental carcinogen’; to hardwood dust which can cause nasal cancer, and to soft wood dust, that if inhaled can irritate the respiratory system or interfere with mucociliary action.

There are also possible environmental effects associated with the process. The major emission from any chipboard factory is formaldehyde, but analysis by University of Liverpool researchers found highly dangerous dioxins in the ash emitted from the Sonae factory.5

Image: Sonae chipboard factory, Liverpool

The complaints of health problems affecting local people are typical of those from communities living close to chipboard plants. Those living within the range of the Sonae plant chimney or near to the clouds that rose from the huge piles of dust stored in the open air outside the factory complained of respiratory problems, recurrent illness, and regularly found their cars and gardens coated in the dust.6It is those issues that are behind a class action due to begin next summer and likely to be the biggest in British history.7

Elsewhere, we have documented in much more detail the management culpability for serious environmental harms as well as injuries to plant workers over a period of more than a decade.8 We have also documented a remarkable level of regulatory contact involving a series of local regulators and plant and site management, a relationship we summarised as ‘regulatory tolerance’ on the part of the local and national state. More generally, what we find in both the company’s responses to a litany of health, safety and environmental incidents is the recalcitrance on the part of Sonae management in its failure to recognise, let alone rectify, basic underlying and ongoing problems, as well as a sheer antagonism on the part of Sonae management towards the various regulators. From our study there is a clear and continual sense of frustration amongst regulators who appeared toothless in their attempts to rectify those basic problems of management that produced such devastating impacts on the community and on workers in the plant.9

The consistent recalcitrance shown by the company inside and outside the plant is illustrated by an accumulated criminal record that is as long as any we have witnessed in many years observing and writing about corporate crime. To summarise the company’s criminal record that unfolded between the plant’s opening and 2007, Sonae had been convicted in two environmental cases and received at least 18 environmental enforcement notices. In addition it had been convicted in four health and safety cases and had been issued with at least 12 enforcement notices for health and safety offences. Despite threats to institute legal proceedings against us for making this point, we stand by our long standing analysis of this firm as a serious and habitual career criminal.10

None of this would, of course, be apparent in the world of corporate greenwash in which the company had positioned itself. According to Sonae’s website, the company is committed to:

- Sustainable use of natural resources, by saving, reducing, re-using and recycling

- Compliance with legislative requirements relating to all environmental issues

- Improvement in safety, hygiene and health in the workplace

- Minimisation of the impact of its industrial facilities on their locations and on the environment

The company of course prefers its reputation to be defined through greenwashing activities rather than its criminal record. In April 2006, Sonae UK donated £4,000 to the Community Foundation for Merseyside's ‘Green Machine’ Campaign. Its managing director stated that, ‘We hope our input via the Community Foundation for Merseyside and the Green Machine scheme will make a real difference to local initiatives to improve the environment.’11 It would, of course, take a good deal more than £4,000 to fully pay for the costs of the company’s recklessness that includes the leaking of large quantities of harmful and carcinogenic chemicals into the air, the costs of hospital treatment to the injured, full compensation to the bereaved, the huge costs to the local authority of high levels of inspection, the costs of emergency services to attend numerous serious incidents, and so on and on.

Even more remarkable is that the Sonae plant continued to operate through this period. Certainly the scale of fines levied on Sonae did not focus management on plant nor environmental health and safety. Perhaps this is not surprising. For example, in 2002, Sonae UK's annual turnover was about £90 million, so its largest penalty of £40,000 for offences levied in 2003 equated to about 0.04% of turnover for the previous year.

Even in the context of health and safety violations alone, accumulating such an impressive criminal record is no mean feat, given that the Health and Safety Executive operates on a principle of using prosecution as a very last resort and that its regulatory strategy is to bargain, negotiate and reach mutual agreement with employers rather than pursue law enforcement.12 It is also worth noting that, in the same period, at a national level, the total number of health and safety prosecutions had begun to collapse under pressure from the government’s deregulation strategy: for the period covering Sonae’s convictions (between 2000 and 2004), the national rate of prosecutions for health and safety offences fell by a third and enforcement notices by a quarter.

The local authority that had done so much to welcome the company into Kirkby, was also jolted into taking action to curb Sonae’s habitual environmental criminality. Between the factory’s opening and February 2007, Knowsley council served 17 enforcement notices on Sonae for violations of environmental laws, and one notice requiring information, with which Sonae failed to comply.13

But during 2007 there appeared to be signs of change at the plant. One index of this was that management at the plant signed a recognition agreement with the trade union UNITE. Moreover, the local campaign group fell silent – in retrospect, more an all too common case of campaign burnout. In fact, Sonae appeared to drop off the local political and media agenda from 2007 until late 2010. In the four years between February 2007 and late 2010 Sonae claimed to have cleaned up its act and there were no prosecutions of the company during this period, despite the fact that between a February 2007 fire and the end of 2010, there were four major fires at the plant.

Image: One of numerous fires at the Sonae factory, June 2011

The trade union voice from within the plant was also relatively silent on the question of the safety record of the plant. It is perhaps unsurprising that workers in the plant might be reluctant to speak out on questions that are clearly highly sensitive for their employer. It is more surprising to find silence on the part of regional officials representing a unionised factory with such an appalling safety record. This silence is probably indicative of the desperation for jobs in Kirkby, and certainly there was visible hostility at some local campaign meetings between those members of the community who demanded closure of the plant, and those who worked at the plant.

On Tuesday, 7 December 2010, the hiatus in both regulatory activity and local popular and political attention was to end. On that day, two sub-contractors undertaking maintenance work, Thomas Elmer, 27, and James Bibby, 25, died after being dragged by a conveyor belt into a silo machine.14This seemed to attract the attention of a local media hitherto relatively disinterested in the plant’s track record, as both the Liverpool Echo and the Daily Post ‘revealed’ the ‘”Shocking” safety record at Kirkby’s Sonae factory’.15 At the time of writing this the inquest into those deaths is ongoing, and no decision on prosecution has been made.

In June 2011, six months after the two sub-contractors had died, another major woodchip fire broke out at the plant. Four firefighters were injured when initially attending the incident. The fire burned for 8 days, causing complaints from neighbouring estates which were engulfed in foul-smelling black smoke. Sonae’s management took the decision to dismantle the fire-damaged buildings. Two months after the fire, in the course of that work, came a third death at the plant, that of Denis Kay.

On Saturday, 6 August 2011, Dennis Kay, a demolition contractor employed by Andrew Connolly Demolitions, was killed whilst working on a cherry picker. As he was leaning over the cage of the platform the cherry picker rolled up into a steel girder, crushing Kay’s head and body. Nigel Graham, managing director at Sonae Indústria (UK) Ltd, announced that the plant would be temporarily closed ‘as a mark of respect’; it reopened two days later. Exactly two months after the death, Merseyside Police, who had been investigating the incident with the Health and Safety Executive, concluded that there was no criminal case to answer.16 If they did not prompt a law enforcement response, these deaths did reignite local community opposition to Sonae and early in 2011 a new community group, Say Bye to Sonae, emerged to organise demonstrations and public meetings.

The plant reopened in December 2011, following what Sonae’s management claimed was a £25 million refurbishment.17 The following year, and after another major fire, Sonae commenced further refurbishment at the plant – albeit prior to receiving planning permission from the Council and in the knowledge that objections had been lodged to this application. When this was revealed through the local media, Sonae sought retrospective permission. Eventually, as discussions with the council continued, Sonae announced it would be closing the plant with immediate effect in a press release dated 14 September 2012. ‘The decision’, ran the release, ‘is the result of the long delays to the reconstruction of the factory due to political and licensing difficulties and the reduced and unsustainable capacity levels that have ensued.’18 Thus, said Sonae managing director Nigel Graham on the same day, ‘our trading position is no longer commercially viable.’19

Image: Community protests against Sonae

Sonae is a global operation, claiming to be the largest chipboard manufacturer in the world, and running similar plants in eight different countries. Kirkby residents are by no means the only community that is drawn into conflict with the nuisance neighbour. In the Sonae plant in White River, South Africa local people have protested against an upgrade of the plant, fearing that pollution is going to get worse. In 2007, local campaigners in White River won demands for an Environmental Impact Assessment to be conducted by government regulators. The Assessment found that not only ‘were the levels of dust, noise and smells coming from the factory unacceptable’, but that ‘readings for formaldehyde in the air at the perimeter fence were five times higher than they ought to be’.20 Yet, just as in Kirkby, plant management have continued to deny its pollution, and lie about the environmental problems its factories cause.21 Sonae’s Chief Executive has denied that most of the airborne formaldehyde came from the Sonae plant, but rather that the problem was pollution from ‘cars and cigarettes’, while blaming other factories in the area.22 One resident of White River has noted that the community is ‘actively fighting the activities of the plant, but we feel a little like butterflies fighting a thunderstorm…’ 23

The case of Sonae raises two questions that run deeper than the management or organisation of the factory. First, it raises a question about the extent to which the production of chipboard using the type of process used at the Kirkby plant could ever be made safe. This question is brought into sharp relief by the installation of a higher chimney stack, announced by the company in 2005 to disperse smoke better and cut smells. This, according to Sonae UK managing director Tony Hackney, was the key change that showed ‘we want to make a new start.’ Yet the effect of the chimney was to spread the smells and dust to other parts of the city, depending upon which way the wind was blowing. Residents of other areas further afield particularly have complained about smells and dust. MP for West Lancashire, Rosie Cooper MP, has noted that as a result of the higher stack, ‘my constituents in Simonswood fear for their safety.’24

Second, it raises a question about the ongoing complicity of local politicians and their regeneration fetish. In Kirkby, the local residents have fought a campaign that has forced their local MP and the company to take measures to deal with the safety of the plant. They may have felt, just like their South African counterparts, as if they were caught like butterflies in a thunderstorm. But it remains the case they have been much more effective in challenging this multinational firm than politicians that are supposed to represent their interests. Despite their extensive resources and legal powers, the local authority and local MPs have been aimlessly flapping around waiting for their fairytale regeneration story to come true. It never did come true. And as we await the biggest class action in UK history, we now know it never will.

Image: Workment pull down Sonae factory chimney, 2013

Footnotes

1 See Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley, Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy, 2001,http://www.knowsley.gov.uk/resources/154112/contaminated_land_strategy.pdf:28

2 Watson, J. (2004) ‘MP to Hold Protest Talks about Sonae’, Liverpool Echo, 30 July.

3 McFall, L. (2001) 'Shut Danger Plant', Liverpool Echo, 6 March.

4 Knowsley Against Toxic Sonae (n.d.) Report of the Result of a Health Questionnaire Carried out in Northwood, Kirkby, to Examine the Effects on Public Health and Quality of Life of Emissions from the Sonae Chipboard Factory, Kirkby: KATS.

5 Liverpool Echo, 30 November 2000.

6 ‘Sonae’s Legacy of Pollution and Ill Health’, TVS Magazine, November 2001.

7 Liverpool Echo, 1 May 2012. In January 2013 Sonae admitted responsibility for the fire and willingness to provide compensation for those affected: ‘A spokesperson from Sonae Industria said: "Regarding the admission of breach of duty related with the fire in June 2011, the question of whether anybody has suffered an injury, which is recognised in law and is entitled to compensation, will be the subject to further detailed investigation by the court.”’ ‘Sonae admit fire liability as 10,000 Kirkby residents claim for compensation’, Liverpool Echo, 29 January, 2013,http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/sonae-admit-fire-liability-10000-3326022

8 Tombs, S and Whyte, D (forthcoming, 2014), ‘Toxic Capital Everywhere: mapping the co-ordinates of regulatory tolerance’, Social Justice, vol. 42.

9 Ibid.

10 In December 2006, a letter from solicitors under Sonae’s instruction was sent to the Nerve web hosts threatening legal action related to a damaging effect on Sonae’s reputation and ordering an article posted in Spring 2004 be removed within seven days. In 2004, we described Sonae as a ‘habitual criminal’ for its dangerous and polluting activities at its Kirkby plant in a piece written for Nerve (Nerve 3, Spring 2004). The article was later posted on the Kirby Times website. Subsequently the company instructed solicitors to send libel letters to the web hosts, eventually resulting in the article and others with similar claims being removed from the website (Nerve 10, Spring 2007). In response to the company’s legal offensive we delved a bit further into Sonae’s criminal record and found a string of prosecutions and serious incidents since 2004 which led us to conclude that the company was ‘serious repeat offender’ (Nerve 10, Spring 2007).

11 Daily Post, 3 April 2006.

12 See, for example, Tombs, S and Whyte, D (2010) ‘A Deadly Consensus: worker safety and regulatory degradation under New Labour’, British Journal of Criminology, 50/1: 46-65; and Tombs, S and Whyte, D (2010) Regulatory Surrender: death, injury and the non-enforcement of law, London: Institute of Employment Rights.

13 Hansard, 27 Feb 2007, col. 990; and see Hansard, 1 May 2007: Column 1588W for a breakdown of the complaints and notices.

14 BBC News (2010), ‘Two workers killed at Merseyside chipboard factory’, 7 December, seehttp://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-11940850

15 Liverpool Daily Post, 16 December 2010 and Liverpool Echo, 16 December 2010.

16 Liverpool Echo, 20th August 2011.

17 Liverpool Echo, ‘Anger as Sonae plant re-starts production of chipboard’, 21 December 2011

18 Sonae Indústria Announcement. 14 September, 2012. See,http://www.sonaeIndústria.com/file_bank/press/announcements/Comunicado_Encerrramento_UK_ENG.pdf

19 BBC News Online (2012) ‘Knowsley Sonae chipboard factory closure’, 14 September. See,http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-19604851

20 Attwood, M. (2008) ‘When the Wind Blows’, Noseweek, 109, November. Seehttp://www.noseweek.co.za/index.php?current_issue=109

21 Sonae lies to South African residents about Sonae in Kirkby. Seehttp://www.liverpooltimes.net/2008/05/18/sonae-strikes-again/#more-1173

22 Private communication, 28 September 2007.

23 Private communication, 01 August 2007.

24 Hansard, 27 Feb 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment