It is Jails and Cops friday at Scission.

Black August ain't no movie.

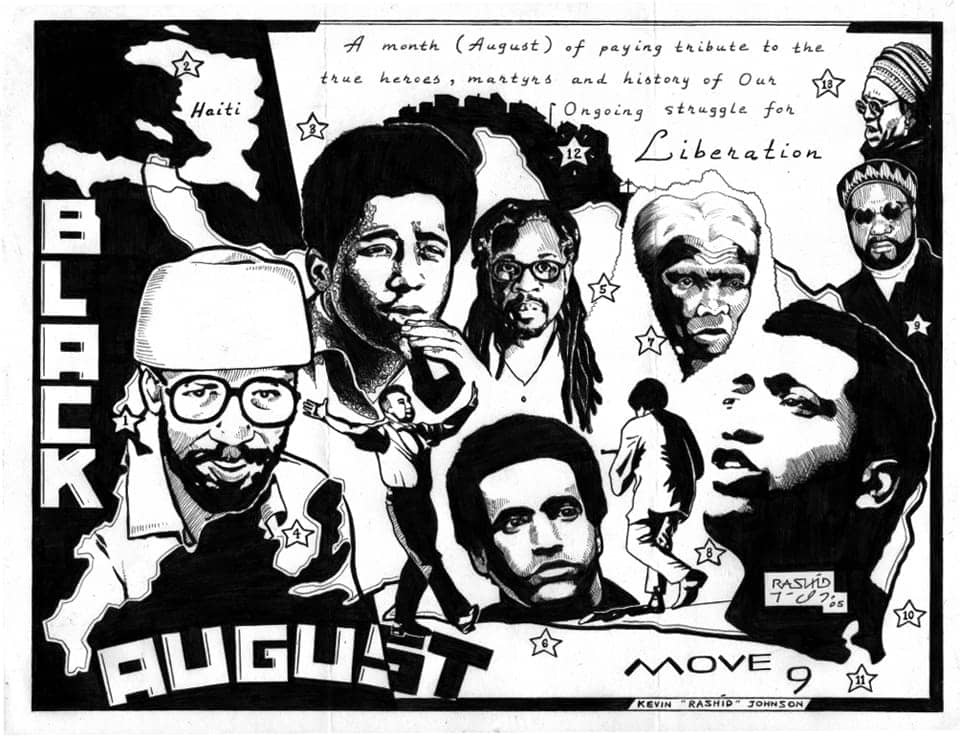

Black August originated in the prisons of California to honor fallen Freedom Fighters, Jonathan Jackson, George Jackson, William Christmas, James McClain and Khatari Gaulden. Jonathan Jackson was gunned down outside the Marin County California courthouse on August 7, 1970 as he attempted to liberate three imprisoned Black Liberation Fighters: James McClain, William Christmas and Ruchell Magee.

I guess I could try and explain this myself, but instead I will turn to a description I found from way back in 2005 on the Assata Shakur Forums page.

Black August originated in the California penal system to honor fallen Freedom Fighters, Jonathan Jackson, George Jackson, William Christmas, James McClain and Khatari Gaulden. Jonathan Jackson was gunned down outside the Marin County California courthouse on August 7, 1970 as he attempted to liberate three imprisoned Black Liberation Fighters: James McClain, William Christmas and Ruchell Magee. Ruchell Magee is the sole survivor of that armed liberation attempt. He is the former co-defendant of Angela Davis and has been locked down for 38 years, most of it in solitary confinement. George Jackson was assassinated by prison guards during a Black prison rebellion at San Quentin on August 21, 1971. Three prison guards were also killed during that rebellion and prison officials charged six Black and Latino prisoners with the death of those guards. These six brothers became known as the San Quentin Six.

Khatari Gaulden was a prominent leader of the Black Guerilla Family (BGF) after Comrade George was assassinated. Khatari was a leading force in the formation of Black August, particularly its historical and ideological foundations. Khatari, like many of the unnamed freedom fighters of the BGF and the revolutionary prison movement of the 1970's, was murdered at San Quentin Prison in 1978 to eliminate his leadership and destroy the resistance movement.

The brothers who participated in the collective founding of Black August wore black armbands on their left arm and studied revolutionary works, focusing on the works of George Jackson. The brothers did not listen to the radio or watch television in August. Additionally, they didn't eat or drink anything from sun-up to sundown; and loud and boastful behavior was not allowed. The brothers did not support the prison's canteen. The use of drugs and alcoholic beverages was prohibited and the brothers held daily exercises, because during Black August, emphasis is placed on sacrifice, fortitude and discipline. Black August is a time to embrace the principles of unity, self-sacrifice, political education, physical training and resistance.

In the late 1970's the observance and practice of Black August left the prisons of California and began being practiced by Black/New Afrikan revolutionaries throughout the country. Members of the New Afrikan Independence Movement (NAIM) began practicing and spreading Black August during this period. The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) inherited knowledge and practice of Black August from its parent organization, the New Afrikan People's Organization (NAPO). MXGM through the Black August Collective (now defunct) began introducing the Hip-Hop community to Black August in the late 1990's after being inspired by New Afrikan political exile Nehanda Abiodun.

Traditionally, Black August is a time to study history, particularly our history in the North American Empire. The first Afrikans were brought to Jamestown as slaves in August of 1619, so August is a month during which Blacks/New Afrikans can reflect on our current situation and our self-determining rights. Many have done that in their respective time periods. In 1843, Henry Highland Garnett called a general slave strike on August 22. The Underground Railroad was started on August 2, 1850. The March on Washington occurred in August of 1963, Gabriel Prosser's 1800 slave rebellion occurred on August 30 and Nat Turner planned and executed a slave rebellion that commenced on August 21, 1831. The Watts rebellions were in August of 1965. On August 18, 1971 the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) was raided by Mississippi police and FBI agents. The MOVE family was bombed by Philadelphia police on August 8, 1978. Further, August is a time of birth. Dr. Mutulu Shakur (political prisoner & prisoner of war), Pan-Africanist Black Nationalist Leader Marcus Garvey, Maroon Russell Shoatz (political prisoner) and Chicago BPP Chairman Fred Hampton were born in August. August is also a time of rebirth, W.E.B. Dubois died in Ghana on August 27, 1963.

The tradition of fasting during Black August teaches self-discipline.

Or to put is more simply, from Killu Nyasha,

Black August is a month of great significance for Africans throughout the diaspora, but particularly here in the U.S. where it originated. "August," as Mumia Abu-Jamal noted, "is a month of meaning, of repression and radical resistance, of injustice and divine justice; of repression and righteous rebellion; of individual and collective efforts to free the slaves and break the chains that bind us."

Well, August is almost over, but Black August will live on.

The following is borrowed from Dissent.

From Freedom Summer to Black August

San Quentin prison (Gino Zahnd/Flickr)

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer, when thousands of mostly white college students from around the country traveled to Mississippi to contest segregation at its most violent source. Commemorations of the momentous civil rights campaign appropriately highlight the black political participation that has grown as a result of those heroic voter registration efforts and seems symbolically reflected in the two-time election of the nation’s first black president.

There is another anniversary of black protest this year that has received less attention. Thirty-five years ago California prisoners founded Black August, a holiday to pay tribute to African-American history in the context of an ever-expanding carceral state. In a kind of secular activist Ramadan, Black August participants refused food and water before sundown, did not use the prison canteen, eschewed drugs and boastful behavior, boycotted radio and television, and engaged in rigorous physical exercise and political study. Through Black August, prisoners sought to demonstrate the personal power they maintained despite incarceration.

Black August celebrations have always been somewhat subterranean, and all the more so in recent years when some prison officials have used reprisals such as long-term solitary confinement to punish those who organize for better conditions. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that prisoners in several states, including California, Pennsylvania, and Georgia—all states that have witnessed prisoner strikes in recent years—continue to honor at least some aspects of the holiday.

Whereas this summer has seen many celebrations of Freedom Summer’s influence on expanding black communities’ access to the institutions of U.S. democracy, Black August marks a less pleasant but no less dramatic reality of American politics. It points to the racialized exclusions that continue to haunt the American experience—especially in the form of the expansive prison industrial complex that makes the United States the world’s leader in incarceration. In remembering histories of black activism from the space of prison cells, Black August points to the ongoing failure to realize the promises of freedom and democracy that drove the civil rights activists of the 1960s.

A Prison-Made Holiday

Black August began in California’s San Quentin in August 1979. The men who founded the holiday wished to commemorate the rich, tragic history of prison protest over the past decade as well as the number of historically significant events in the black freedom struggle that have taken place in the month of August. “We figured that the people we wanted to remember wouldn’t be remembered during black history month, so we started Black August,” cofounder Shuuja Graham told me.

For the founders, the month of August was also significant for tragic reasons. In 1971 imprisoned intellectual and Black Panther George Jackson was killed in a bloody uprising. His seventeen-year-old brother, Jonathan, had been killed the previous August attempting to free three prisoners from a Marin County courthouse. Both events caused an already tense prison system to crack down on prisoner access to media and to the public. Their subversive study groups became more clandestine, as violence among prisoners and between prisoners and guards increased in frequency. And those who wished to press for social change from inside the prison faced steeper obstacles to participating in political organizations.

Black August points to the ongoing failure to realize the promises of freedom and democracy that drove the civil rights activists of the 1960s.

Then on August 1, 1978, Jeffrey Khatari Gaulden was killed during a game of touch football in the San Quentin prison yard. Someone pushed him too hard, and he hit his head as he fell to the ground. As the other prisoners clamored for medical attention, guards cleared the yard one person at a time, searching each person individually. By the time the prisoners were cleared, Gaulden had bled out. The thirty-two-year-old had been imprisoned since 1967, and was inspired by the likes of George Jackson to become a militant activist. He makes few appearances in the records of California’s prison movement before his death, though he was well known among Bay Area prison activists and well respected among other men of color in the California prison system. He was convicted in May 1972 for killing a civilian laundry worker at Folsom the previous September, allegedly in retaliation for Jackson’s death. The incident occurred just after Gaulden was released from solitary confinement, and he was returned there after his conviction.

To his compatriots, Gaulden’s death signaled the decline of what had once been a vibrant movement for prisoner rights. Black August was a way for them to honor him and other activists. As the holiday continued, adherents identified a variety of other significant events that had occurred in August. There were slave rebellions, from the beginning of the Haitian Revolution (August 21, 1791) to those attempted by Gabriel Prosser (originally scheduled for August 30, 1800), launched by Nat Turner (beginning August 21, 1831), and called for by Henry Highland Garnett (August 22, 1843). There were deaths (W.E.B. Du Bois, August 27, 1963) and births (Marcus Garvey, August 17, 1887; Garvey’s organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, formed in August 1914). And there were protests, from the UNIA’s month-long international convention of 25,000 people at Madison Square Garden in August 1920 to the 1963 March on Washington, from the Watts rebellion of 1965 to the 1978 standoff between police and the black naturalist organization MOVE in Philadelphia.

Black August was not the first protest of its kind. Prisoners in New York had organized “Black Solidarity Day” earlier in the 1970s in protest of racism in prison. But for a variety of reasons, Black August is the one that took hold. The early celebrations inside the prisons were matched with small protests at the gates of San Quentin. And social networks of activist organizations carried Black August from prison to prison in Illinois and New York, Georgia and North Carolina, and places in between. But by the early 1980s, few people were paying attention to the worsening conditions inside prisons.

More recently, the history of Black August has been taken up in hip hop circles and other groups in New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area. In Oakland, the Black August Organizing Committee has held movie showings, organized summer programs for youth, and advocated for political prisoners. Other organizations, including the Eastside Arts Alliance and the Freedom Archives, have organized events showcasing the history of Black August in relation to contemporary racial justice organizing. The New York–based Black August Hip Hop Project organized annual events between 1998 and 2010, including “international delegations of artists and activists to Cuba, South Africa, Tanzania, Brazil, and Venezuela.” Black August concerts have included artists such as The Roots, Mos Def (now Yasiin Bey), and Erykah Badu, among many others. Black August has bled into the culture of a new generation. While it is difficult to track exact numbers, especially in California, where marking the history of George Jackson and Black August still finds prisoners facing disciplinary sanction, some dissident prisoners continue to honor the tradition alongside its extension into the world of hip hop. Black August, a celebration of black diasporic radicalism, has itself gone diasporic.

Unbloodied by History

In the 1960s, Mississippi wore its white supremacy on its sleeve. The Sunflower State took pride in its stark racial order, and the signs were everywhere to be seen, detailing which water fountains, restaurants, and restrooms were for “whites” and which ones for “coloreds.” These signs were not just visual: they could be heard in the bellowing pronouncements of the state’s segregationist officials and felt in the police truncheons and putrid cells of the notorious Parchman Prison.

By 1964 the visibility and vitriol of Mississippi’s apartheid had reached the national stage, and the state seemed to epitomize the backwardness of Jim Crow. With Freedom Summer, the Southern civil rights campaign reached its crescendo: the noble pursuit of basic human rights in the face of storybook villains who boasted of their cruelty was laid bare for all to see. That summer, and the landmark civil rights legislation it inspired, nurtured a definition of racism that revolved around dramatic spectacles of open violence in defense of an unjust and archaic system.

California, in contrast, not only looked peaceful but actively presented itself as far removed from racism and unpleasantness of all kinds. True, the 1965 Watts rebellion—which left thirty-four dead and hundreds of millions of dollars in damage—challenged that idyllic image. So did a series of ballot initiatives that kept in place housing and employment segregation. But as activists discovered across the country, often in the wake of uprisings and riots, attempts to defeat racism in the North and West were routinely stymied by the complex institutional factors upholding police brutality, residential segregation, employment discrimination, and educational inequity. Too many officials believed their cities and states to be exempt from the kind of evil so obviously perpetrated in the South.

At the dawn of mass incarceration, the creators of Black August saw that racism itself was being reinvented or at least being updated through the criminal justice system.

California perfected this kind of racial innocence. “One difference between the West and the South, I came to realize in 1970, was this: in the South they remained convinced that they had bloodied their land with history,” essayist Joan Didion wrote in her memoir. “In California we did not believe that history could bloody the land, or even touch it.” That difference between Mississippi and California, the difference between an acknowledged bloody history and its disavowal, found expression in California’s prison policies. It is part of why Black August emerged there rather than in Mississippi or elsewhere.

After the Second World War, California had pioneered a liberal form of prison management called bibliotherapy. It was a philosophy that believed expanded literacy among incarcerated people would prove rehabilitative. Instead, it proved radicalizing, and the state prisons churned out people who were hyper-literate and militantly opposed to the racism they experienced in prison and in their home communities of Los Angeles and Oakland. Men such as Huey P. Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and Alprentice Bunchy Carter left prison and built the Black Panther Party; others, such as George Jackson and Khatari Gaulden, contributed to this black radical upsurge without ever leaving prison.

In response, state officials abandoned bibliotherapy. They placed new restrictions on the number of visitors and the types of publications people in prison could receive. They expanded solitary confinement units. By the early 1980s, they launched the biggest prison construction project in world history. As geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore writes, California’s “prisoner population grew nearly 500 percent between 1982 and 2000, even though the crime rate peaked in 1980 and declined, unevenly but decisively, thereafter.” The state built twenty-three prisons, “thirteen community corrections facilities, five prison camps, and five mother-prisoner centers” between 1984 and 2007. California was early to experiment with the “three strikes” system and mandatory minimum sentences that contributed to the massive spike in the number of prisoners since the 1970s. After the Second World War, the state was seen as a leader in rehabilitative “corrections”; after consolidating the shift toward retribution that began in the 1970s, it has since the 1980s been a leader in punitive policing and imprisonment.

California has always fancied itself a place of reinvention. At the dawn of mass incarceration, the creators of Black August saw that racism itself was being reinvented or at least being updated through the criminal justice system. Black August commemorated histories of black radicalism and practiced ascetic personal discipline to call attention to the many ways that history continued to bloody the land—now in the form of prisons and ghettoes. Racism was not bad people nurturing ancient prejudice; it was solitary confinement and unfunded schools. A state that thought itself unbloodied by history littered the land with prisons, giving us the greatest human rights crisis now facing our country.

Remembering Freedom

Memory matters. What we remember, what we commemorate, says something about the kind of society we imagine ourselves to be living in. Of course, memory is selective; selecting certain details, people, events is always at the expense of other stories we might tell. As several commentators have noted, the Manichean story of nonviolent resistance to Southern segregation overlooks the prevalence of armed self-defense among black Southerners and others, traditions that later inspired the Black Panther Party to pick up arms. The “I have a dream” speech recycled every second Monday in January freezes Martin Luther King, Jr. in time, while his many passionate declarations for economic justice and an end to U.S. militarism are overlooked. The list goes on and on, every memorial a well-intentioned act of forgetting.

The stories now being told about Freedom Summer righteously celebrate the bravery of the thousands of civil rights workers who brought down Jim Crow segregation. Their contributions to bringing democracy to the United States deserve our highest praise and deepest reflection. But such commemorations should not lull us into the false sense that their mission has been completed. A popular civil rights slogan during the summer of 1964 demanded “Freedom Now.” With some attention to Black August and its surrounding histories of prisoner organizing, especially in light of such high-profile police murders of unarmed black men, this summer’s commemorations might point out how much work is left to do before we can say that the United States has let freedom ring.

Dan Berger is the author of Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era, among other titles. He is an assistant professor of comparative ethnic studies at the University of Washington Bothell. Follow him @authordanberger or on www.danberger.org.