It was a dream of the late Mayor of Jackson Mississippi, Chokwe Lumumba, to turn Jackson into a center of economic democracy building cooperatives, worker owned enterprises and financial institutions. The Mayor is dead but the dream lives on.

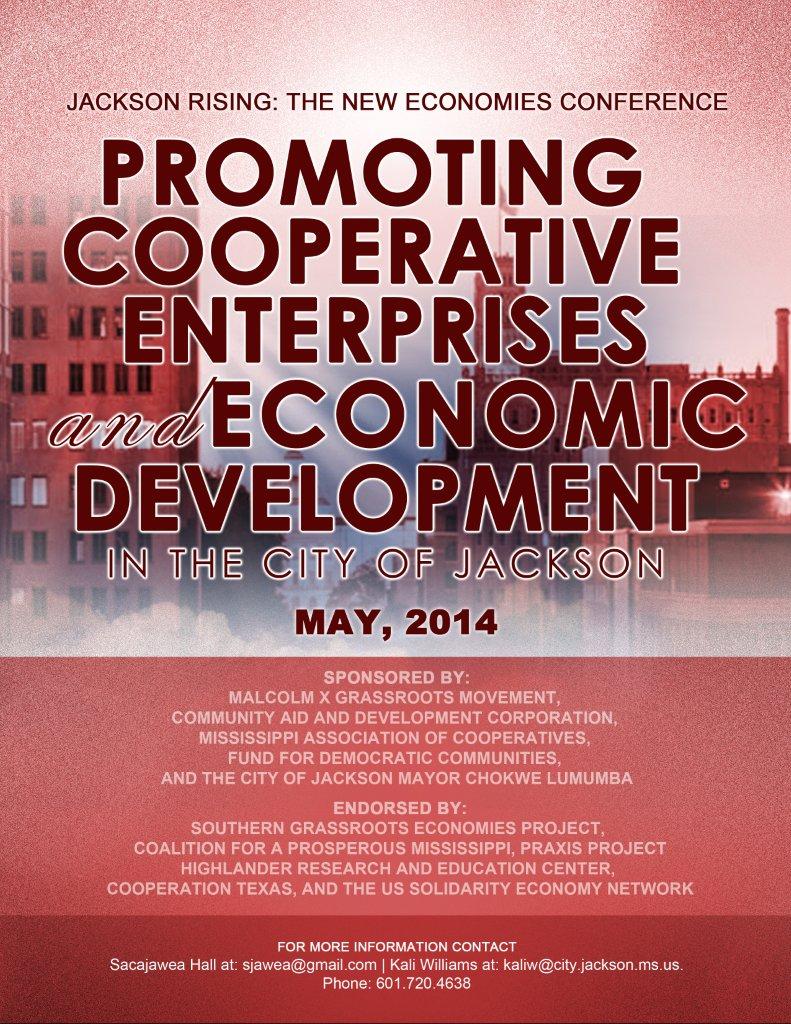

Last week the Jackson Rising Conference was held at Jackson State University. The purpose of the conference was to encourage Jacksonians to build cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises in order to meet the economic and sustainability needs of the community. The primary objective of the Conference was to:

...educate and mobilize the people of Jackson to meet the economic and sustainability needs of our community. In the process, we aim to expand the discussion about alternative economic models and systems - and to confront the harsh economic realities of low-income and impoverished communities.

The conference went on despite the fact that the City Council which last February unanimously approved a resolution to support it, suddenly announced it was not designating funds or resources to the event.

And then there were the usual fools like Jim Cunningham, president of Mississippi for Liberty who said,

It’s concerning that our taxpayer-funded universities are sponsoring events that espouse what appears on the surface to be nothing more than thinly veiled communism.

Jim, as a communist, I can assure it was not that.

I am not a big believer in co-operatives of just any kind, but still, this conference was far ahead of most...and not your old hippie grocery store. Kali Akuno, a Jackson Rising coordinator, commented in the Jackson Free Press that the movement is based largely on the experience of black Americans:

It's a chapter of our history that has long been suppressed and forgotten in many respects. What were the mutual-aid societies that were created in the 1700s, not only in the North, but also in the South? Folks collectively pooled their resources together, to bury their dead, to have weddings, to buy land together. These are things that go back some 200-plus years.

Jessica Gordon Nembhard, a professor of African American studies at the University of Maryland and author of a new book "Collective Courage" on African American cooperatives writes,

African Americans throughout their history have come together to pool resources, take control of productive assets, and work to create alternative economies in the face of poverty, limited resources, market failures and/or racial oppression.

Many of the processes have been similar: Join together in the face of a need or a problem, start small and spread the risk widely, use mutual group self-help as motivation, and continuously engage in education and training. Through their modest economic empowerment efforts, many of the groups were able to win greater battles against white landowners, white unions and general economic underdevelopment.

Hey, I can dig that.

The white ruling class did not.

There was a vicious backlash when black co-ops threatened the status quo.

The white economic structure depended on all of these blacks having to buy from the white store, rent from the white landowner. They were going to lose out if you did something alternatively.

In an interview with Truthout, Nembhardt points out it hasn't all been about business and enterprises either,

Definitely for slavery we're talking about informal cooperative economics, not an official co-op business, but just collectively raising money to buy somebody's freedom. One person might buy themselves out and then they would save money to buy their mother or daughter, their wife or their father - that kind of thing. That level of collectivity, people even consider the Underground Railroad to be a kind of collective activity, sort of collective economics, sharing of resources, that kind of thing. The more official relationships I found were what's called mutual aid societies.

It was certainly done clandestinely. Often it wasn't done by slaves, but it would be done by freed people because slaves in some ways couldn't even bury themselves since they didn't own their own bodies. In some ways a lot of these were more once you had a freed population, but some of it would be enslaved, because sometimes they were able to make a little bit of money on the side. If you had a skill, on Sundays you could hire yourself out. Some of the families would have a tiny, little garden by their cabin so they could sell some of that. So, there was a way to make a little bit of money and they tried to pool that to help each other. But a lot of the mutual aid would be through freed people, and there were freed populations during slavery.

There is a basic problem though with economic cooperatives, worker owned cooperatives economic models (beside the fact that if Capital ever actually feels threatened by such its response will be swift and hard). They retain, what John Spritzler writing at New Democracy says is,

...one of the most important defining characteristics of the capitalist model with which we are so familiar today: production of commodities to be sold for a profit in the market place.

The real problem is that the cooperative is trying to function within a capitalist society and trying somehow to avoid the pitfalls that must follow. One of the many problems then is put forth here by Zoltan Zigedy,

Until recently, cooperators and their advocates had one very large arrow in their quiver.

When pressed on the apparent weakness of cooperatives as an anti-capitalist strategy, they would counter loudly: “Mondragon!”.

This large-scale network of over 100 cooperative enterprises based in Spain seemed to defy the criticisms of the cooperative alternative. With 80,000 or more worker-owners, billions of Euros in assets and 14 billion Euros in revenue last year, Mondragon was the shining star of the cooperative movement, the lodestone for the advocates of the global cooperative program.

But then in October, appliance maker Fagor Electrodomesticos, one of Mondragon's key cooperatives, closed with over a billion dollars of debt and putting 5500 people out of work. Worker-employees lost their savings invested in the firm. Mondragon's largest cooperative, the supermarket group Eroski, also owes creditors 2.5 billion Euros. Because the network is so interlocked, these setbacks pose long term threats to the entire system. As one worker, Juan Antonio Talledo, is quoted in The Wall Street Journal (“Recession Frays Ties at Spain's Co-ops”, December 26, 2013): “This is our Lehman moment.”

It is indeed a “Lehman moment”. And like the Lehman Bros banking meltdown in September of 2008, it makes a Lehman-like point. Large scale enterprises, even of the size of Mondragon and organized on a cooperative basis, are susceptible to the high winds of global capitalist crisis. Cooperative organization offers no immunity to the systemic problems that face all enterprises in a capitalist environment. That is why a cooperative solution cannot constitute a viable alternative to capitalism. That is why an island of worker-ownership surrounded by a violent sea of capitalism is unsustainable.

The failures at Mondragon have sent advocates to the wood shed (seewww.geonewsletter.org). Leading theoretical light, Gar Alperovitz, has written in response to the Mondragon blues: “Mondragón's primary emphasis has been on effective and efficient competition. But what do you do when you are up against a global economic recession, on the one hand, or radical cost challenges from Chinese and other low-cost producers, on the other?”

What do you do? Shouldn't someone have thought of that before they offered a road map towards a “third way”? Are “global economic recessions” uncommon? Is low cost production new? And blaming the Chinese is simply unprincipled scapegoating.

Alperovitz goes on: “The question of interest, however - and especially to the degree we begin to face the question of what to do about larger industry - is whether trusting in open market competition is a sufficient answer to the problem of longer-term systemic design.” Clear away the verbal foliage and Alperovitz is admitting that he never anticipated that open market competition would snag Mondragon. Did he think that Fagor sold appliances outsideof the market? Did he think that Mondragon somehow got a free pass in global competition?

Of course the big losers are the workers who have lost their jobs and savings. It would be mistaken to blame the earnest organizers or idealistic cooperators who sincerely sought to make a better, more socially just workplace. They gambled on a project and lost. Of course social justice should not be a gamble.

Many years back already, the Basque Workers Council, a syndicate combining class and national demands, was critical of Mondragon (based in their neck of the woods) since it was formed. In their magazine, they charged the cooperatives with:

Becoming like any private firm, from the point of view of daily work, the cooperative member is exploited in his/her job in a capitalist firm by increased production, mobility, schedule changes, etc.

We don’t understand why the managers don’t present a proposal to lower the age of retirement in the cooperatives…Instead, they opted, just like owners of private firms, to achieve profitability by the same methods as capitalist firms: lay-offs, increasing productivity, temporary contracts, etc.

Are cooperatives an improvement over your run of the mill capitalist enterprises? Sure. Are they an alternative? I suppose they are a capitalist alternative. Are they a communist alternative? I think not. Are they worthwhile in the fight against capitalism? Probably, so in the war of position waged by the multitude.

Do I wish the Jackson Rising Campaign success?

Absolutely!

Am I an expert on the co-operative movement or Mondragon? Nope. I offer my comments with humility. If you want more in depth analysis of these things, you will have to find it on your own. I simply do not see anything that has to operate within a capitalist milieu as being able to separate itself and become some sort of island of communism, not today, not in an era of Empire. Cooperatives are not the goal and they are not a stage on the way to communism. It just does not work that way.

Or so I think anyway.

Many people whom I respect agree with me.

Many other people whom I respect do not.

The following is from Black Agenda Reports.

Jackson Rising: Black Millionaires Won't Lift Us Up, But Cooperation & the Solidarity Economy Might

Printer-friendly version

By BAR managing editor Bruce A. Dixon

“...activists from all over the country, including 80 or more from Jackson and surrounding parts of Mississippi converged on the campus of Jackson State University for Jackson Rising....”

For a long time now we've been fed and been feeding each other the story that uplifting black communities means electing more faces of color to public office and creating more black millionaires. Those wealthy and powerful African Americans, in the course of their wise governance, their normal business and philanthropic efforts can be counted on to create the jobs and the opportunities to largely alleviate poverty and want among the rest of us. The only problem with this story is that it's not working, and in fact never really did work.

It was a myth, a fable, a grownup fairy tale which told us nothing about how the world and this society actually functioned.

In the real world, we now have more black faces in corporate board rooms, more black elected officials and more black millionaires than ever before, alongside record and near-record levels of black child poverty, black incarceration, black unemployment, black land and wealth loss. The fortunes of some of our most admired black multimillionaires, like Junior Bridgeman and Magic Johnson, rest firmly on the continued starvation wages and relentless abuse of workers in his hundreds of fast food and other restaurants.

Over the first weekend in May about 320 activists from all over the country, including 80 or more from Jackson and surrounding parts of Mississippi converged on the campus of Jackson State University for Jackson Rising. They came to seek and to share examples of how to create not individual success stories, but stories of collective self-help, collective wealth-building, collective success and the power of mutual cooperation.

The hundreds gathered at Jackson Rising spent the weekend exploring and discussing how to fund, found and foster a different kind of business enterprise – democratically self-managed cooperatives. They reviewed future plans for and current practices of cooperative auto repair shops, laundries, recycling, construction, and trucking firms. They discussed cooperative restaurants, child and elder care coops, cooperative grocery stores, cooperative factories, farms and more, all collectively owned and democratically managed by the same workers who deliver the service and create the value.

Participants at Jackson Rising learned a little of the story of Mondragon, a multinational cooperative enterprise founded in the Basque country, the poorest and most oppressed part of Spain. That country now has about a 25% unemployment rate, but in the Basque country where Mondragon cooperatives operate factories, mines, retail, transport, and more, the unemployment rate is 5%. When a Mondragon factory or store or other operation has to close because of unprofitability, Mondragon retrains and relocates those workers to another of its enterprises. Mondragon's cooperative ethos makes it so different from other enterprises, one representative explained, that they're about to have to offer their own MBA program, to guarantee they get trained managers without the bloodsucking, predatory mindset taught and valued at most business schools. They heard that Mondragon is now partnering with the UFCW and local forces to establish cooperative grocery stores and enterprises in Cinncinnati.

Those attending Jackson Rising heard about the concept of a solidarity economy, an economy not based on gentrification or exploitation or the enrichment of a few, an economy based on mutual cooperation to satisfy the needs of many, to stabilize neighborhoods and communities, to provide needed jobs and services.

Cooperation, or as it's sometimes called, “the cooperative movement” is a model that is succeeding right now in tens of thousands of places for tens of millions of people around the world. It's a model than can succeed in the United States as well. The dedicated core of activists in the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, MXGM, after deeply embedding themselves locally in Jackson Mississippi and briefly electing one of their own as mayor in the overwhelmingly black and poor city of half a million, are determined to show and take part in a different kind of black economic development.

To that end, they've formed what they call “Cooperation Jackson,” with four short term objectives

- Cooperation Jackson is establishing an educational arm to spread the word in their communities about the distinct advantages and exciting possibilities of mutual uplift that business cooperatives offer.

- When Mayor Chokwe Lumumba was still in office, Cooperation Jackson planned to establish a “cooperative incubator.” providing a range of startup services for cooperative enterprises. Absent support from the mayor's office, some MXGM activists observed, a lot of these coops will have to be born and nurtured in the cold.

- Cooperation Jackson aims to form a local federation of cooperatives to share information and resources and to ensure that the cooperatives follow democratic principles of self-management that empower their workers. We've always said “free the land,” observed one MXGM activist. Now we want to “free the labor” as well.

- Finally Cooperation Jackson intends to establish a financial institution to assist in providing credit and capital to cooperatives.

The MXGM activists are serious thinkers and organizers. They conducted door to door surveys of entire neighborhoods in Jackson, complete with skills assessments to discover how many plumbers, plasterers, farmers, carpenters, construction workers, truck mechanics, nurses and people with other health care experience live there, and how many are unemployed. You'd imagine any local government that claimed it wanted to provide jobs and uplift people might do this, but you'd be imagining another world. In Jackson Mississippi, local activists are figuring out how to build that new and better world. The US Census Bureau gathers tons of information useful to real estate, credit, banking and similar business interests, but little or nothing of value to those who'd want to preserve neighborhood integrity and productively use the skills people already have.

In the short run, new and existing cooperatives in Jackson or anyplace else won't get much help from government. Mike Beall, president and CEO of the National CooperativeBusiness Association pointed out that the federal budget contains a mere $7 million in assistance for agricultural cooperatives, and that the Obama administration has tried to remove that the last two years in a row. There was, he said, no federal funding whatsoever to assist non-agricultural business cooperative startups or operations

By contrast, Wal-Mart alone receives $7.8 billion in tax breaks, loophole funds and public subsidies from state, federal and local governments every year, and according to one estimate, about $2.1 million more with each new store it opens. Another single company, Georgia Power is about to receive $8.3 billion in federal loan guarantees and outright gifts for the construction of two nuclear plants alongside its leaky old nukes in the mostly black and poor town of Shell Bluff. When it comes to oil companies, military contractors, transportation infrastructure outfits, agribusiness, pharmaceuticals and so on there are hundreds more companies that get billions in federal subsidies. Cooperatives get nothing. In the state of Mississippi, according to one Jackson Rising workshop presenter, non-agricultural cooperatives are technically illegal.

All these traditional corporations have one thing in common. Unlike democratically run cooperatives which share their profits and power, traditional corporations are dictatorships. Their workers don't, in most cases, have the freedom of speech at work or the opportunity to form unions, and certainly don't get to share in the wealth their labor creates for their bosses. To normal capitalist corporations, those workers, their families and communities are completely disposable. Detroit used to be a company town for the auto industry. When that industry grew and consolidated enough to disperse production in lower wage areas around the world it quickly abandoned Detroit and its people leaving a shattered, impoverished polluted ruin behind.

The new mayor of Jackson, who ran with developers' money against the son of the late Chokwe Lumumba and narrowly defeated him, locked a number of city employees affiliated with the old administration out of their offices immediately after the election, before even being sworn in. The city removed all sponsorship and assistance to the Jackson Rising conference. There was a campaign in local press branding its organizers, communists, terrorists, unpatriotic and unfit to discuss the serious matters of job creation and building local economies. But the conference ran smoothly anyway, with invaluable assistance from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives Land Assistance Fund, an organization that has help save the land and land rights of more black farmers over the last forty years than any other, and the Praxis Project, the Fund for Democratic Communities, the Highlander Research and Education Center, and several others.

“At Jackson Rising, hundreds of movement activists from around the country discovered, rediscovered, began to visualize and explore cooperation and the solidarity economy.”

“This new mayor of ours made a big mistake. What would it cost him, even if he imagines cooperatives cannot succeed, to give his blessing to this gathering?” asked Kali Akuno of Cooperation Jackson. “As an organizer I can now ask why he's against job creation? He's got no answer to that.

“It's hindsight of course, but maybe we should have paid attention to this piece first, and the electoral effort only afterward. Who's to say that if we'd done it that way we would not have been more successful in retaining the mayor's seat.”

This past weekend was the 50th anniversary of the first freedom rides which kicked off the youth-led phase of the southern Freedom Movement. Something of similar importance happened in Jackson Mississippi last weekend.

At Jackson Rising, hundreds of movement activists from around the country discovered, rediscovered, began to visualize and explore cooperation and the solidarity economy. They met with their peers from North Carolina, Ohio, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and of course Mississippi already engaged in pulling it together. It's an economy not based on gentrification as black urban regimes in Atlanta, New Orleans and other cities have and still are doing. It's not based on big ticket stadiums or shopping malls or professional sports teams, none of which create many permanent well paying jobs anyway. It's not based on fast food and restaurant empires that follow the McDonalds and Wal-Mart model of low wages and ruthless exploitation. It's about democracy and collective ownership of business, collective responsibility and collective uplift.

It's coming. Jackson Mississippi is already rising, and your community can do the same. Black Agenda Report intends to stay on top of this story in the coming weeks and months.

Bruce A. Dixon is managing editor at Black Agenda Report, and a state committee member of the Georgia Green Party. He served seven years on the board of a 480 unit housing cooperative in Chicago, and now lives and works near Marietta GA. He can be reached via this site's contact page, or at bruce.dixon(at)blackagendareport.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment