Native Hawaiians are celebrating a victory this week.

Hawaiian activists and farmers announced yesterday victory in a five-month campaign to force the University of Hawaii (UH) to abandon its patents on three varieties of Hawaiian taro it first obtained in 2002.

The agreement to abandon the taro patents was reached in a June 12th meeting between Walter Ritte, a Molokai activist who spearheaded the campaign and Gary Ostrander, UH Manoa Vice-Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education. At the meeting, Ritte delivered a letter signed by him and Kaua'i taro farmer Christine Kobayashi with instructions on the procedure for abandoning, or "disclaiming," the taro patents.

Ritte and Kobayashi first demanded the patents be dropped in a January letter to UH officials. Their demands soon found widespread support in the native Hawaiian and taro farming communities. Three high-profile demonstrations at the University of Hawaii finally forced UH officials to confront the issue.

"University officials never consulted with Hawaiians before obtaining the taro patents in 2002, and it took them a while to realize we were serious about wanting them dropped," Ritte told the Molokai Island Times , who noted that his request to have the issue discussed at a UH Regents meeting on May 18th was rejected.

"A few weeks ago, University officials announced they would transfer the patents to the native Hawaiian community," said Ritte. "We rejected that because we object to anyone owning kalo, even ourselves. Now the patents will be dropped. Haloa instructs us to malama (reverence and protect) kalo, not own it. This concept of turning life into 'intellectual property is foreign to Hawaiian culture, and that's why we need to have a voice in future decisions on Hawaiian biodiversity."

"The taro patent controversy shows the need for UH and other organizations to first consult with the community before genetically modifying or patenting organisms in Hawaii," said Sarah Sullivan, director of Hawai'i SEED, a statewide coalition advocating sustainable agriculture

Activists are now demanding a voice in future decisions by UH and other organizations on intellectual property arrangements involving Hawaiian biodiversity.

For background information see http://oreaddaily.blogspot.com/2006/05/native-hawaiians-protest-patent-on.html.

The following story is from the The Star Bulletin (Hawaii).

Activists tear up 3 UH patents for taro

"It is as if the patents were never filed," said Gary Ostrander, vice chancellor for research at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, who attended the event. "Anyone throughout the world may now plant them, may propagate them, sell them."

Since January, Hawaiians have been pushing the university to give up patents it had obtained on three varieties of disease-resistant taro it developed. The Hawaiians argue that kalo as the "elder brother" of the Hawaiian people should not be owned.

"Today is a victory," said activist Walter Ritte of Molokai, who helped lead the effort to end the only patents on Hawaiian taro. "The university has taken a big step by listening to the people they should be listening to. It's a huge example for other people to follow."

After a leaf blight wiped out 90 percent of the taro in Samoa in the 1990s, Ostrander said, University of Hawaii scientists were asked to help.

They used traditional breeding techniques to cross Palauan and Hawaiian taro to produce three strains resistant to the disease, and the university obtained plant patents on them in 2002.

In January, Ritte and Kauai taro farmer Christine Kobayashi sent a letter to the university demanding that the patents be dropped. Their protest grew, and on May 18, Hawaiians clad in malo padlocked the entrance to the university's medical school in an effort to make their point.

"UH did not invent taro, and they had no right to own it or license it to farmers," Kobayashi said in a written statement yesterday.

After behind-the-scenes negotiations, the university filed "terminal disclaimers" with the U.S. Patent Office that dissolved its proprietary interests as of last Friday. It had issued 13 licenses to use the plant, but licensees no longer owe royalties or any other obligation to the university, Ostrander said.

"I hope this is an opportunity to continue to develop our existing relationship based on mutual trust and respect, as undoubtedly we will face other issues as we go forward," Ostrander said, adding that he had come to appreciate the Hawaiians' point of view on the issue.

"The Hawaiian people have been modifying and growing taro for 1,000 years, and probably 5,000 years before that in Polynesia," he said. "What seems counterintuitive now is that a faculty member can make an improvement now and patent it."

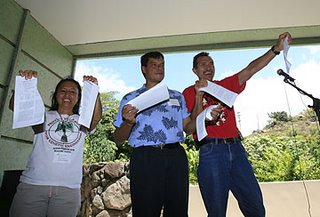

At yesterday's event at the UH Center for Hawaiian Studies, University of Hawaii-Manoa interim Chancellor Denise Konan handed the copies of the patents on three varieties of taro to Kobayashi, Ritte and Jon Osorio, director of the UH Center for Hawaiian Studies. In unison, the three tore them in half.

The patents were on taro plants named "Paakala," "Pauakea" and "Palehua," all known for their vigorous growth, good taste, and resistance to taro leaf blight.

Manu Kaiama, director of the Native Hawaiian Leadership Project, welcomed the university's move, but said it wasn't making a big financial sacrifice.

"They don't have much of a market," she said. "I wonder if the administration would have been willing to give up a patent that was going to make millions of dollars."

Ostrander acknowledged that the patents are "not a big money maker right now" but said interest had been expressed in using the kalo varieties in baby food.

Graduate student Kelii Collier called the patent fight just the first step in a broader movement against other UH undertakings such as a proposed military research center on the campus.

"It is the beginning for the university to do the right thing," he said. "The next time we meet it will be to rip out the UARC (University Affiliated Research Center) contract."

No comments:

Post a Comment