It's late and I just got home, so not much time. Fortunately, I've been thinking of posting this piece and have it right here.

Capital is a big deal, World Cup Soccer is a big deal, repression is a big deal, resistance is a big deal, Brazil is a big deal, Revolution is a really big deal. It is all coming together this summer.

I could have searched for a nice ideologically correct or Marxist oriented article about all this, you know, that type of analysis.

I didn't.

Instead, I thought something from ESPN: The Magazine would actually be better as far as just giving a straight up feeling, a personal look, a relative non political (if such is possible) view on what is happening in Brazil and how it relates to the upcoming World Cup series there this summer.

I know some will complain about it coming from ESPN, but strangely, for the corporate type world of journalism, I find the writing in this hard copy mag to be some of the best around and often the politics ain't to shabby either.

Anyway, ready or not...

Generation June

Fury, anarchy, martyrdom: Why the youth of Brazil are (forever) protesting, and how their anger may consume the World Cup.

The protest outside Brasilia's World Cup stadium in June was about much more than the World Cup itself. Gustavo Froner/Reuters

WHEN I LAND in Rio, I go straight to an Ipanema coffee shop to meet the young woman who founded Meu Rio. She's the first in a series of spiritual guides whose stories will make something as ephemeral as the hopes of a generation come alive for me. They are both the creators and the progeny of the energy felt on the streets.

Alessandra Orofino bounds through the door apologizing for being late, coming straight from a meeting, headed to another one when she's finished with me. She's tiny, with a mop of curly hair, and a contagious laugh. Like many of the new activists, her parents marched to topple the dictatorship in the 70s and 80s. She was born in 1989, the year of the first direct presidential elections since Jango was removed from power by the military. Her mom joined her in protest this June. Some people in the streets that month hadn't marched since the dictatorship finally collapsed in 1985, the old folks telling the kids the trick to tripping police horses: covering the cobblestones with wine corks. Orofino senses that her parents' generation spent so much energy fighting the generals that, once they'd won freedom, they didn't have any energy left. "Which I think is part of the reason you have so many people going out in the streets right now," she says. "There is a sense that the adults are not doing anything."

She noticed something was happening in June when 500 people showed up for a protest about a price hike for the busses. A year earlier, Meu Rio tried to get people in the streets for the same issue and could only manage 200. Orofino canceled a planned trip to New York, understanding something new was surfacing. The next protest, 5,000 people showed up. By the third day of the tournament, 100,000 people marched in Rio alone, and three days later, more than a million people protested government spending and corruption. The poor and the middle class marched together, even the young and the old -- a street coalition that has, throughout the history of Brazil, often signaled the end of one government and the beginning of a new one.

Orofino still hasn't made it to New York for her trip. She cannot imagine disconnecting from the feeling in the streets. "It's really magnetic," she says. "I can't leave Rio right now. There's too much happening."

Sitting at the coffee shop describing this magnetism, she bounces, giddy with excitement. She wheels around, looking for the waitress. There is something I must see, and, no, this cannot not wait.

"Let's get the bill!" she says.

She leads the way to a favela, a Brazilian slum, a few blocks away, and when we arrive, she points up, as if to say: I give you modern Brazil. The building in front of us looks like a modern train station, with an enormous façade, four or five stories into the sky, nearly as wide as it is tall. A tower rises even higher from the main building. It's an elevator to the favela. That's all the building is for. The government doesn't provide running water to the citizens of the favela, but they give them an elevator. Only a sliver of the red brick shanty homes built into the hillside is visible. Officially, the elevator is to give easier access to the favela, and it's just a coincidence that the building is exactly wide and tall enough to block out a mountain and all the poor people who live on it.

In the main lobby, there are only two actual elevators.

One is broken.

The floor of the building shines and glitters in the sunlight. She laughs, howling, her voice rising, incredulous.

"Marble," she says.

PEOPLE LIKE Alessandra believe these obvious injustices can be fixed, and this belief is present wherever young Brazilians gather. One night in São Paulo, I head over to the bohemian neighborhood of Vila Madalena to meet a group of young street photographers who've been at the front line of the riots since June. They crowd around sidewalk tables, still run through with adrenaline and fear from their first kiss of war, drinking ice-cold draft beer and smoking hash. An airy soundtrack of jazz seems to take the whole scene back in time, to every place revolutionaries have gathered in cafes like this one. The alpha dog of the street photographers is named Victor Dragonetti. Everyone knows him as Drago. He's 22.

Drago took the first iconic photograph of June: a cop, with blood running down his face, slumped near a wall, waving a gun around. Two things remain in the memory of everyone who sees it. A disembodied hand reaches in from the left of the frame, a people powerless to stop the madness gripping their society, and there is a look of pure fear in the policeman's eyes, a society powerless to stop the madness of its people. It's a photograph about the helplessness of actors once they've been assigned a role.

Drago is skinny, with a beard that doesn't fully connect to his mustache, and a rumpled coolness. Ask him his favorite book and he'll grin and say, "I play Grand Theft Auto V." He wears a plaid shirt, with a long chain for his medallions of a dragon and of St. George. Jack Daniel's neat is his drink, when somebody else is buying. He's the grandson of the best-looking whore in the blue-collar town of Belo Horizonte.

His life story mirrors that of his generation, cycling through alienation, anger and hope.

His father chopped sugar cane as an eight year old, living on his own at 13, begging for food. At 16, Drago's dad moved to the city, with no money or connections. He took a mechanics class to learn how to fix cars, met a woman, had a child, got divorced. Drago has watched his dad work every day, never managing to get ahead, never being able to buy a home or even a car. One afternoon at a trendy restaurant, Drago looks around and says that even if his father had money, he'd feel too insecure to eat here.

His mom's family had money, and a business, and they took out huge loans to try to make it bigger. They failed. Now only the debt is left, which he will inherit, his financial life ruined before he'd ever worked a day. His heroes, he says, are his mother and father, because they showed exactly how not to live.

June gave him purpose, and a voice, and Drago's life is changing because of it. Yesterday, the most important photography collector in Brazil bought 22 of his pictures. Five months ago, he was unknown, and now Drago's work is considered art, a rapid rise he himself mocks. Tomorrow, Drago finds out if he is the winner of the Esso award for photography, which is like Brazil's Pulitzer Prize. Eight people are nominated, and the other seven are established, well-known photojournalists. At the café, scabs cover both his arms. The stress of waiting to find out if he'll win the Esso has him obsessively scratching and pulling at his skin.

The waiters bring more beers, and a hot cast-iron griddle so the drinkers can cut their buzz with slices of grilled rump steak. Drago mans the tongs, turning the pieces until the fat renders, crisping the thin cuts of meat. The air smells like salt and beef. The other photographers crowd around. Drago raps in Portuguese, a song by a hip-hop star named Criolo, who's become the voice of many people in the streets. He tries to find an American song with the same message, something I'd know. Finally he growls: "F--- you, I won't do what you tell me! F--- you, I won't do what you tell me!"

The next morning, he steps uneasily into the light with a blistering hangover, wearing last night's clothes, his shirt unbuttoned, the sun shining on his dragon and his St. George medallion. He squints through sunglasses he borrowed from his girlfriend's sister, pulls a black fedora down low. A cigarette burns between his lips. Every few minutes for hours, he's been hitting refresh on his phone, reloading the Esso website, waiting for news on the contest. Now it has arrived. He dials his father, who still fixes cars and will one day leave this world as poor as he entered it. His dad answers the phone.

"I won the f---ing thing!" Drago says, his voice rising with laughter, his coolness momentarily discarded. He is quiet while his father talks, then he laughs again. Drago invites his father to the ceremony in Rio. There's a pause. No one is laughing now. His father is saying something from his heart. Drago finally replies.

"I love you, dad," he says.

This award-winning photo by Victor Tavares Dragonetti, known as Drago, captured the moment a wounded police officer pinned a protester and pointed a gun at the group that had just hit him during the June demonstrations. Drago/DOC Galeria

WE FOLLOW the youth, moving through fractured modern Brazil.

One strange day, I march across Rio, shadowed by riot cops with their fingers on the triggers of tear gas launchers. Then I drop my gas mask and combat helmet at a five-star Copacabana hotel, take a cab ride, give my name to a guy with a list and I'm backstage in the dressing room of Criolo, the rapper whose lyrics have inspired Drago. The open-air amphitheater is packed with young people hungry for his message.

Criolo himself took to the streets in June, finding his old childhood friends in his old neighborhood, and marching to the bus station, seeing the eyes of teenagers find strength in the famous rap star alongside them. "Each person in his daily routine starts realizing that they are not alone," Criolo says. "The routine massacres us. It's a miracle when we realize that we are still alive."

He leans in very close when he talks.

"Revolution happens every day," he says.

The sudden exchange of riot gear for a backstage floating with models and bottles of scotch is disorienting. I hang out in the hall, waiting for the show to begin. My translator stands next to me, a cool Brazilian unimpressed with most everything, until he sees a serene old man with dreadlocks inching past. His eyes grow wide.

"Milton Nascimento," he whispers. "A legend."

Before Criolo, there was Nascimento. He fought the military dictatorship with his music -- a weaponized falsetto. The dictatorship put secret police outside record stores to see which people appeared to like singers of his generation. Nascimento's songs give the history of the Brazilian protest movement. "A Student's Heart," one of his most famous, is about the funeral of a Brazilian student named Edson Luís, whose murder by police in 1968 put hundreds of thousands of middle class citizens into the streets, bringing down violent repression from the dictatorship. Seventeen years later, as the generals relinquished power and a protest movement demanded direct presidential elections, the same song provided the soundtrack for the millions of Brazilians who marched. The killing of Edson Luís was Brazil's Kent State, and Nascimento was Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

How can you run when you know?

WHEN YOU MEET the people on the streets since June, and those who marched after the death of Edson Luís, 2013 begins to echo 1968. The two generations of protesters share many things, but there remains a simple yet unbridgeable difference: Those who were young in 1968 are now old, and they know what time did to their dreams.

João Neto marched in 1968, and on this afternoon in São Paulo, sitting at a table for the lunch buffet at his neighborhood tennis club, he learns for the first time that his 16-year-old son, João Paulo, took part in the protests of June. A father both treasures and fears the pieces of himself that he sees in his son, and Neto knows what can happen. He was the martyr Edson Luís' close friend, and he was standing next to him when he got shot.

Edson Luís died in his arms.

João Neto remembers March 28, 1968, and all the events that brought him there. When Neto begins to speak, his son focuses on his father, eyes locked and intense. The noise of the restaurant fades away, until the whole universe exists in the words coming out of Neto's mouth.

He goes back in time, to the spooky waters of the Negro River. He grew up on its banks in the 1960s, surrounded by the Amazonian rainforest. He read the news that found its way to his frontier post office. It seemed like the world was about to catch fire, students taking to the streets. When he looked around, all he saw was endless jungle and a dark flowing river, and people who would live and die without ever believing that the facts governing their existence could be changed at all, much less by them. He needed to get out, and in 1967, he started college in Rio, working to pay his way.

That's where he met Edson Luís. Edson grew up poor in the Amazon, too, a shy boy, always hungry. Working in the cafeteria, every day he ate once with his friends, and then again in the kitchen, taking as much food as he could get. Their lives revolved around the cafeteria, especially for the poorest among them.

That's where Edson ate his last meal.

They'd been protesting continuing inequality and as the fourth anniversary of the 1964 military coup approached, they gathered at the cafeteria to take to the streets again. The police closed in to stop the protest before it began. Forty-five years later, sitting in a room that has gone from empty to full while he told this story, Neto takes out a piece of paper and draws the cafeteria and the location of the cops circling it.

The descriptions come in short bursts now.

Cops barged in the door, maybe 50, holding revolvers and nightsticks.

Someone shouted, "Run!"

He and Edson left their trays at the table and bolted for the door. Some students used trays as shields. Others flung them at the police. A student threw a rock, and an officer fired three or four shots into the crowd. Neto remembers the roaring bang, and when he looked to his right, he saw the blood spreading on his friend's shirt. Edson didn't have any last words, or speak any revolutionary slogans. He just moaned. Neto fell to the ground to help, and so much of Edson's blood soaked his shirt that he ran his hands over his own chest, looking for the bullet wound.

Edson died with his eyes open. He was 18 years old.

They rushed their friend to a hospital a block away. An orderly tried to revive him, but the bullet had torn a hole in Edson's heart. His friends refused to take the body to morgue, scared the government would never release it, so they carried him to the state legislature, shouldering his bloody corpse past slack-jawed politicians and putting it on the heavy table at the front of the room.

They covered Edson's body in signs protesting the dictatorship. He'd died holding his geometry homework, so they rested that beneath his head. Fifty thousand people took to the streets for the funeral. Neto helped carry the casket. Middle-class citizens, who'd been quietly resentful of the dictatorship they'd once supported, rallied around the young mourners. In the fancy buildings of Flamengo, people threw flowers out of their windows in support. As the sun went down, people lit candles, so Edson Luís made his way to his final resting place past hundreds of flickering windows. The streets were full. Neto felt empty. Six days later, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis.

The history books in Brazilian classrooms describe the chaos that followed Edson's death. The middle class citizens went from supporting the students to joining them. Cops shot protesters. Some of those captured were tortured. Others just disappeared. On June 26, 1968, during the famous March of 100,000, musicians and movie stars joined housewives and students and nuns. In Brazil, the generals realized they had lost popular support, eventually responding with an end to even the appearance of democracy. They passed the famously repressive law, AI-5, which shuttered Congress and eliminated most rights of citizens, from voting to habeas corpus, plunging the nation into a period known as "the years of lead."

Forty years later, in 2008, the government dedicated a sculpture to Edson Luís. Many politicians and former guerrilla leaders showed up. Edson's mother, Maria, came from the Amazon, 84 years old and near death, and in all the photographs, her expression never changes, stern and hard, as if her son had only died a few minutes before.

Today, the statue is rusting and the base is falling apart after only five years, pieces ripped open by the humidity and the rain. On the main pillar of the monument, in white paint, one of the two major drug gangs that dominate Rio has graffitied a machine gun. On a recent day, people come and go through the plaza and nobody stops to look.

THE GHOSTS OF 1968 have followed João Neto. For years after, he used the numbers of Edson's grave, 14-602, to play the lottery. He's taken his son, João Paulo, to the site of the former cafeteria, which is now a parking lot owned by the city of Rio. The place feels sacred to Neto, and he sometimes cries there. He shows his son the alleys where he ran from cops, and the church where he spent the night, drinking the Holy Water to quench his thirst.

João Paulo smiles.

He's heard the Edson Luís stories before.

"A lot," he says, laughing. "Many times."

Sitting at the table eating their usual lunch of rice, beans and steak, Neto now tells his son a story he'd never told him before.

He wore his bloody shirt -- soaked with the blood of his friend, Edson -- to the hospital, and the wake, and the funeral, and afterward, he went to his uncle's house in Rio to sleep, still wearing the shirt.

"What happened to you?" his uncle said.

"This is Edson's blood," he said.

He refused to let his aunt wash the shirt, and before falling into fitful sleep from which he's never really awakened, he put the bloody garment into a plastic bag. He buried it in a drawer in his home, and for decades, that's where it stayed. His involvement in the student movement followed him wherever he want, causing him to lose out on some jobs, stall in others without explanation. Eventually everything that happened to him could be viewed through the lens of 1968 -- measuring the facts of his life with the hopes a younger him had for it. One day, he reached into the drawer, took out the tan shirt with the brown strip, covered in dried blood. It was falling apart. He tossed it into a trash can, an exorcism of sorts. He fumbles through reasons why he threw it away, each answer getting a little closer to the truth, until he finally says, "It didn't make any more sense to carry the past."

Edson's assassination started a movement -- a boy evolving into an idea -- and the lives of those who were there in the beginning have fallen short of the promise of that moment. Something was born when Edson got shot, but eventually something died, too, a belief in what a generation could accomplish, which is probably why Neto swells when he hears his son talk about marching this past June, even as he worries, too. He looks at his son and sees what he used to be. Maybe his son can finish what he began. João Paulo is 16, the age when Neto moved to the city from the Amazon.

"Do you remember the 16-year-old you?" I ask.

"Perfectly," Neto says.

João Paulo argues with his father about the atmosphere in the streets in 2013, explaining that it isn't 1968 any longer, and that while some things are the same, many things have changed forever. He believes what he is saying, even as he is surrounded by evidence that he's wrong.

"It's a totally different moment," João Paulo says. "They are not going to kill me like they killed Edson."

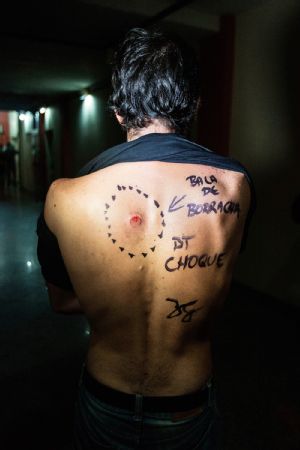

AN HOUR LATER, in a poor neighborhood in the far north edge of São Paulo, a mother who used to have a son opens the door to her home. The only difference between her and Edson Luís' mother is time. Her name is Rosana Martins. Seventeen days ago, she had a son. Douglas Martins Rodrigues was 17 years old and liked to change the color of the rubber bands in his braces.

Now only pieces remain.

Rosana picks up his worn backpack by the door and unzips it. In the front pocket, there's a flimsy umbrella. Another jagged breath escapes her lips. His cell phone is there, guarded by a SpongeBob case, and she caresses that. She pulls out his notebook.

Most of the pages are blank. She flips to the last assignment he ever did. His handwriting is neat, almost girlish. The ink is blue, filling almost one and a quarter pages with sentences written in English. Can I help you, sir? … Where could I get a bus/underground to go to a soccer stadium to see a match? … Oh, it's easy. You walk down this street/avenue two blocks. … I suggest you, first of all, a sightseeing tour. She stands there crying, and it dawns on me what he was learning to do. There was confirmation at the top of the first page, where he wrote the name of the assignment: World Cup in Brazil 2014.

The police shot Douglas in the heart as he walked to the corner store with his brother. An accident, they said, and the cop is being charged with manslaughter. The family said the cop approached Douglas with his gun drawn, pointed at the kid, the kind of pro-active violence human rights activists claim happens all the time in Brazil. The family thinks their boy's life didn't matter, just another poor kid off the streets. It's one more notch on the gun barrel of the government. They killed Edson Luís. They killed Douglas, and now his mother goes into his bedroom, where the closet still smells like teenage boy. She picks up a small T-shirt made for his 5-year-old sister to wear to the funeral. The little girl requested the phrase written on it: "Douglas has gone to live in heaven."

Rosana cannot let go of the knowledge of how he spent his last minutes. When the bullet hit his chest, the first thing he said was: "Why did you shoot me, sir?" He called his murderer "sir." In the ambulance, with only a few minutes to live, he kept asking why. He realized he was going to die and asked the EMTs to tell his family goodbye. His mother rushed to the scene in time to see the ambulance, but they wouldn't let her inside.

In his bedroom, she touches his last remaining inhaler.

He always struggled to breathe, suffering from asthma and frequent bouts of pneumonia. When he was a boy, she took him to the hospital, protected him, stood by his side during the scary procedures, comforted him when he struggled to take one deep breath. Tears roll down her face, so many it takes two hands to wipe them all away. In his final moments, as he died, he complained that he couldn't breathe, and his mother wasn't there to hold his hand.

People protested Douglas' death for a few days, even shutting down a big highway, carrying signs, but the anger faded. Nothing changed. Two boys were killed by the police the day after Douglas died and nobody protested at all. The history of Brazil, however, is clear on this matter. There is a line. One of these bodies will be a body too many, or one exposed corruption will be a graft too far, and the youth will fill the streets, and the middle class will support them, verbally at first, then side-by-side, a small protest of 500 growing exponentially in a few days until a million people march down Rio Branco Avenue toward Cinelândia.

Brazil is a spark away.

A SMALL GROUP of 25 or 30 Black Bloc protesters gather in Cinelândia and set off across Rio de Janeiro, carrying signs and a black flag. I strap on my gas mask and blend in with the anarchists. We walk for miles, surrounded by police, shutting down avenues and highways and a tunnel, the demonstration small and harmless and odd, yet always one hot temper from a full-on battle in the middle of the most famous beach in the world. The protesters hand out fliers explaining their actions. A man crumples the paper into a ball, throwing it onto the ground. A young anarchist runs back and picks up the flyer, staring down the man who discarded it. Over and over, the Black Bloc chant: "Come! Come to the streets, come!"

One person joins the march.

This generation found a cause, and they found each other, and they found a collective voice. If they haven't changed Brazil, they rattled it, but as 2013 bleeds into 2014, the momentum of June's Confederations Cup is fading away, and a fact is inescapable: They haven't changed Brazil. It remains corrupt. The police remain violent. The spark that will send a nation back into the streets hasn't arrived. But it's more than that. Because a trip to Brazil isn't simply gas masks and helmets. There are also sunsets, and laughter, and the white sand of Copacabana Beach. Many people are just excited for the bread and circus of a huge sporting event, and a growing middle class wants to protect a newly found entry into the consumer culture. A movement was born, but while it was growing, and then shrinking, many people their age wanted to play foot volley on the beach and drink frosty liters of Antarctica Original, to look toward the specifics of their own lives with hope and joy.

Generation June is face-to-face with the realization that usually pushes people from the glittering hope of youth toward the dreary pragmatism of middle age: dreams don't always come true. In six months, they've lived an entire life cycle on fast forward, experiencing all the things that take aim at innocence, from fear to comfort, from cynicism to violence. "Here we have these students who are so full of hope that they can change the world," explains Julio Jeha, a university professor who marched against the dictatorship decades ago. "They are starry eyed. You look at them and think, 'Oh, my God, they don't know what they're up against.'"

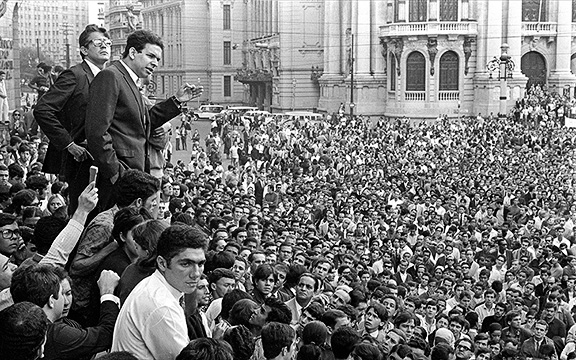

Three days later, I sit in the office of Marcelo Freixo, the beloved left-wing politician who ran for mayor of Rio in the last election, taking on the powerful political machine of the ruling party. He lost but connected with young people, building the base of support. Freixo might be the future, and on the wall of his office, he keeps a window into the past: an enormous poster of the biggest protest march in 1968, prompted by the death of Edson Luís.

He says everyone is asking the wrong questions about the generation created by June, looking to see if any specific things have been changed, missing the fact that the most important change is the birth of the generation itself. Brazil took to the streets in 1968 but didn't topple the generals until 1985. Change takes time, but the agents of that change have been created. June not only birthed a generation of involved citizens, he says, but it convinced a country that the status quo might be vulnerable. June might have bridged the gap between what young people dream and what older citizens think can come true. Immediately after the protests of the Confederations Cup in June, the teachers went on strike and marched, braving police violence, pushing for change. The entire professional soccer league threatened to strike together if a delinquent club didn't pay its players, organizing for the first time in league history.

"There is a cultural rupture," Freixo says. "There was a common sense in Brazil that believing things in Brazil were unfair and would never be changed. After what happened this year, nobody says that anymore."

The next afternoon, on my last day in town, the Occupy movement packs up most of its outpost on Cinelândia. Some make promises about returning, and continuing the fight, but it sure looks like the end. Game Over calls off his hunger strike, eating an energy bar, then a hot dog from a vendor on the square.

Tinker Bell closes a rolling suitcase and stuffs a floppy straw hat into her "I heart Rio" beach bag. She is taking it back to her home in Copacabana. She carries the bag, and Game Over helps her, rolling the suitcase across the square. There is something profound about watching them leave, former lovers, disappearing into the crowd. Maybe they'll find each other again in six months, hardened and ready to change Brazil forever, or maybe this was just a fevered dream of youth.

I'M STILL UNABLE to answer the question the people will inevitably ask when I get home: what's going to happen during the World Cup? Nobody knows, not even the actors. The essential truth of Drago's iconic photograph grew with each passing day in Brazil. Something's been set in motion, and nobody can stop it, or predict where it will go. Many different groups stand in opposition, but perhaps no conflict is more important than the one between the young people and themselves. Will they hold on to their belief? Or will it be ground out of them?

There's a moment I keep replaying from that night out with Drago and the young photographers. It's a cloud over everything I've seen since. We drank beer for hours, and the guys passed around iPhones, showing off their best riot shots. These were the last days of a spring that has given them purpose and hope, most for the first time. A 53-year-old photographer, Fernando Costa Netto, looked around at the young men and women in the cafe. An idea worked inside of him. Past midnight, the young photographers talked about changing the world, and the older photographers talked about being young.

"They think they are immortal," Fernando said.

He smiled, happy to feel the secondhand energy of the things they believe, melancholy he can no longer believe in those things himself. Long ago, he took his camera to Bosnia and the world he saw through his lens showed him the limits of both youth and his art. The heavy wheels of history roll over anything in their way, without pity or nostalgia.

He sighed.

"I thought I was immortal, too," he said. "Not anymore."

ONE MORE STOP back in time remains.

I take a taxi to the Saint John the Baptist Cemetery. The sun seems to rest on the shoulders of the Christ the Redeemer statue, which looks down over the graves from a nearby bluff. It is shockingly hot, soaking a shirt a minute out of the cab. This is where the young mourners buried Edson Luís all those years ago, where they left him when they passed through the cemetery gates to begin the rest of their lives. When I leave a half hour from now, I'll be shaken, trying to process what I learned. It's disturbing, both because of the facts hidden here, and because nobody in Brazil seems to know. For the life of me, I still can't figure out what to make of the discovery, whether it's "Ozymandias," an allegory about nihilism and decay, or a gospel, about the ability of an idea to survive even death.

I search for 14-602.

The grave is a drawer built into the back wall of the cemetery, a bright white glare in the sun, without any relief or shade. Dead vines hang down over the space. Something is wrong. I check the numbers again, and then check them again. The square marked 602 doesn't have a name. I knock against the concrete, and the space sounds hollow.

There is no body inside.

In the office, a bored-looking man goes to the back and returns with the heavy black book from 1968, flipping through yellowed pages … 55 … 56 … 57. He runs his fingers down the page until he stops: record number 3258, a student who was assassinated. The bullet entered the thorax, piercing the heart and the right lung. The record misspells his name and contains no contact information for his family.

I see why his grave was empty. Stamped on his entry are the words "Exhumed June 9, 1973." Five years passed and, per procedure, the cemetery wanted more money. Nobody came forward, and they didn't contact Edson's mother, so the cemetery removed his bones. They took them to an oven, incinerating Brazil's most famous student martyr, whose death changed a country, or maybe didn't change anything at all. They sealed the hole with brittle, quick-dry concrete, and they threw his ashes away.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com. Follow him on Twitter at@wrightthompson. Flavio Ferreira contributed to this report.

Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader. Follow ESPN The Magazine on Twitter: @ESPNmag. Follow ESPN FC on Twitter: ESPN FC.

In a show of social unrest, a man wrapped in a Brazilian flag sits among 594 soccer balls on the lawn of the National Congress in Brasilia. Wilson Dias/AFP/Getty Images

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteexactly , the Issuer TV Globo call manipulates the people , I believe that an agreement with the Lula government has made the Olympics and the World Cup was ' thrown ' into the country, a great deal. Lula is too smart to accept two events of this magnitude , knowing that we are still a country with 13 million people living in poverty . Is suspected . Even though at that time , living a promising econimia , had principles , who are now sample for all Brazilians, and estrageiros hoping to see . Besides , a super - exploitation of the country , which suffocates its citizens ! the country is ' the most expensive in the world ' . To reach this stage , not only a substantive set of economic misconceptions was necessary. It took a lot of ideological blindness to swallow the mantra that our trophy "the most expensive in the world " was achieved exclusively through higher taxes and higher costs trabalhistas.Afinal , years of hard work allowed the Brazilians have the pleasure of paying twice on the same car that other mortals buy without much sacrifice. Besides pizza for $ 30 , dearest casolina . A mango that you take from Mango tree normaly, it costs $ 2 , which are subtracted , the poor wages of the Brazilian people , and that £ 675

ReplyDeleteNo, my friends . Only in a world ( such that some liberals live ) without countries like France, Germany or Sweden Brazil had the highest taxes . If we compare ourselves to the U.S. , we see that the per capita tax contribution of a Brazilian ( $ 4,000 ) is much smaller than that of an American ( U.S. $ 13,550 ) .

All this in exchange for audience and false progress , because progress , private.